Feature

The Evolution of Fashion Watches

The Evolution of Fashion Watches

No doubt, this sort of design-led watchmaking already existed and can be traced back to the late 1990s and early 2000s when independent watch brands began producing watches of extreme design that were — make no mistake — achieved only through creative mechanics. But when brand persona and aesthetic are parlayed into the equation and embedded in the design, layout and complication of a movement, something new emerges from this union that merits more than a niche appreciation.

HERMÈS

Throughout most of the 20th century, Hermès watches were made by major watch companies ranging from Universal Genève to Jaeger-LeCoultre and Rolex, meaning they were expressly produced for Hermès, double-signed and retailed in the latter’s boutiques. It was only in 1978 that the company established its own watch manufacture La Montre Hermès, in Biel, Switzerland to piece together watches designed in Paris.

As with many other watch companies during the quartz age that survived by bringing their so-called enemy into the party, Hermès started producing quartz- powered shaped watches right out of the gate that played to the brand’s equestrian heritage; timepieces that might be termed “fashion watches.” However, the mechanical watch renaissance at the turn of the 21st century became an opportunity for renewed growth. In the same way Hermès vertically integrated the production of objects such as tabletop, crystal glass and porcelain, it approached watchmaking with dogged completeness.

The first of its foundational investments took place in 2006 with the purchase of a quarter share in movement maker Vaucher, a sister company of Parmigiani. Hermès then acquired a stake in case maker Joseph Erard Holding in 2011, before taking over the company entirely by the end of 2013. In between, it added dial maker Natéber to the mix.

Slowly, in-house movements made their way into the house’s most famous shaped watches — the Heure H, Cape Cod and Arceau. But what moved the needle for Hermès was the launch of Arceau Le Temps Suspendu, Dressage L’Heure Masquée and Slim d’Hermès L’Heure Impatiente — a trilogy of poetic timepieces in which mechanics become a statement of a philosophy that is as much about watchmaking as it is about time itself. In these watches, time is portrayed as a hermeneutic experience; a qualitative, rather than quantitative experience of life.

The Hermès Arceau Le Temps Suspendu that playfully stops time — pushing the button at nine causes both hands to snap to an unreadable position at 12 o’clock while the date retrograde hand disappears behind the chapter ring

This was soon followed by L’Heure Masquée, or “The Masked Hour,” in 2014. The watch came by its name for having an unconventional hour hand that remains hidden behind the traditionally running minute hand until it is activated on demand to display the correct hour by a pusher integrated in the crown. However, as soon as the pusher is released, the hour hand disappears beneath the minute hand once again. With only the minutes shown at any given time, it offered a looser structure of time. Apart from the fleeting revelation of the hour, the watch also displayed a second time zone in an aperture at six o’clock, whose hour also remains hidden under a shade with a generic “GMT” inscription until the pusher is depressed, revealing the second hour, along with the hour hand. The second time zone is set by means of a second pusher at nine o’clock. Both the base movement and module were developed entirely in-house by Vaucher.

In 2017, Hermès unveiled its third installation, Slim d’Hermès L’Heure Impatiente, which emphasized the state of anticipation. Housed in the Slim d’Hermès case introduced in 2015, L’Heure Impatiente measures the time of imminent expectation by enabling the wearer to set the counter at five o’clock to the time of the eagerly awaited event that will take place in less than 12 hours. An hour before it occurs, a retrograde timer at six o’clock begins a countdown, announcing the event’s arrival with a sonorous ping.

In recent years, Hermès began on a similar endeavor with Jean-François Mojon and his firm, Chronode, this time offering a poetic take on traditional complications. It launched Arceau L’Heure de la Lune to much fanfare in 2019. The watch offers a simply stunning and stimulating interpretation of a moonphase complication with the use of two subdials that orbit above a pair of moons to display their current phases in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres.

The Arceau L’Heure de la Lune features a pair of floating subdials that orbit the dial to indicate the waxing and waning of the moon in both hemispheres

The Arceau Le Temps Voyageur has a satellite subdial that displays local time, which is automatically updated once the dial aligns with the city ring

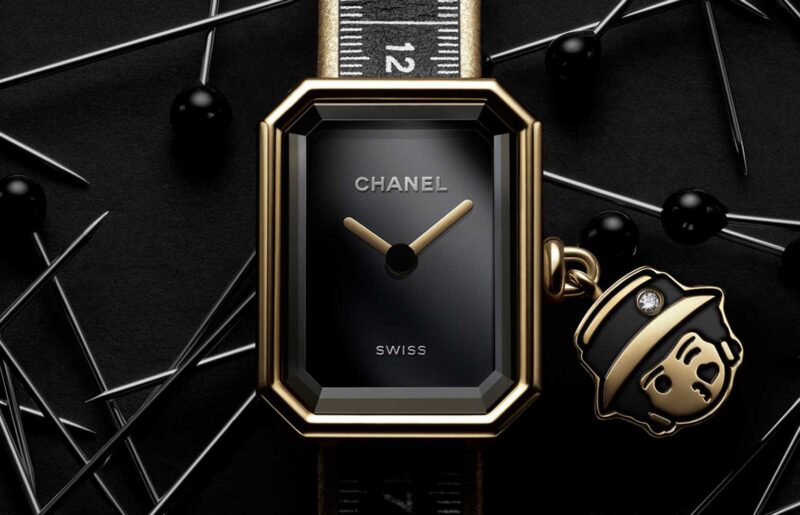

CHANEL

Like many of its peers, the production of Chanel watches was initially subcontracted to external Swiss manufactures. The company made its first horological investment in 1993 by acquiring its case and buckle supplier G&F Châtelain. The latter is responsible for producing the ceramic case and bracelet of the J12, which was launched in 2000 and has since become an icon of modern watchmaking and one of the best-selling women’s watches the world over. The case-making facility in La Chaux-de-Fonds now serves as the headquarters for Chanel’s watch division today.

Up until recent years, Chanel relied on external specialists the likes of ETA, Sellita and Dubois-Dépraz for workhorse movements and Audemars Piguet Renaud et Papi (APRP) for premier movements. The caliber 3125 that powered a black ceramic and gold limited edition J12 (H2129) in 2008 was a variation of the Audemars Piguet caliber 3120. It was subsequently followed by the J12 Rétrograde Mystérieuse Tourbillon, which featured a complex and highly unusual tourbillon movement made by APRP with a retrograde minute hand, a 10-day power reserve and a frontally operated crown.

But a key piece of the puzzle was Chanel’s investment in independent watchmaker Romain Gauthier in 2011. An engineer by training, Romain is best known for his superbly constructed and finished movements such as the innovative Logical One and the Insight Micro-Rotor, one of the finest self-winding timepieces in watchmaking. His highly nuanced movements are made possible due to his ability to produce a majority of components including barrels, gears, shafts, balances and even screws from scratch at his workshop. As such, he also supplies Chanel with key components for high-end movements such as the Caliber 1 in the Monsieur de Chanel and aids Chanel’s eight-person team in La Chaux-de-Fonds in the development of such movements.

The Monsieur Marble Edition with a dial crafted from white-veined black marble

However, the watch that first set the watch world on fire was the abovementioned Monsieur de Chanel in 2019. Not only was the Caliber 1 developed internally, but it was also executed with an exceptional level of sophistication both in terms of its movement design and complication.

The parts that make up one of Chanel’s greatest hits, the Monsieur de Chanel. Notice that there is no additional plate apart from the mainplate, as the jumping hour and retrograde minutes complication is integrated in the movement

With the visual identity of the brand ingrained in both movement and dial design — themselves seamlessly integrated — it achieves a visual purity of coherence, and unity of form and content that are unrivaled by its Swiss counterparts. To top it off, the choice of digital typeface echoes the octagonal jumping hour window, itself reminiscent of Chanel’s perfume bottle stopper while the balance wheel is in the shape of Chanel’s comet.

Following the Caliber 1, Chanel soon unveiled the Calibers 2 and 3 in the Première Camélia Skeleton and the Boy.Friend Skeleton respectively. They were a pair of skeletonized time-only form movements with equally considered and distinctive architectures characterized by circularity. The Caliber 3 even spawned a 3.1 version in the J12 X-Ray wherein the movement plate and bridges were made entirely from sapphire. But last year, the brand unveiled its first in-house flying tourbillon, the Caliber 5 in the J12 Diamond Tourbillon. While the movement echoes the design and finish of the Caliber 1, it was built from the ground up as a tourbillon movement. That it is emphatically aesthetic-driven is less of a surprise; the real surprise was the consideration paid to optimizing the volume of the movement for greater performance within that constraint.

The J12 Diamond Tourbillon housing the superbly engineered Caliber 5

As such, the motion works are off-centered, leaving the tourbillon free from obstructions; the aperture size for the tourbillon, like the barrel, can also be taken to its limit, occupying half of the movement’s diameter for maximum visual effect. The fact that technical excellence has a place in the strive for artistry and coherence in movement and dial design — with respect to the codes of the house — is incredibly impressive and a tough act to follow.

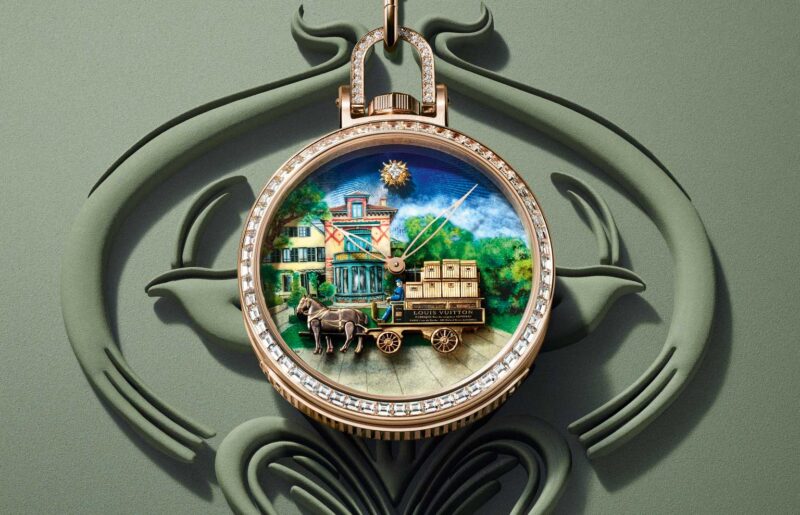

LOUIS VUITTON

The first watches by the world’s most celebrated trunk maker were developed and produced in 1988 by IWC for Louis Vuitton, which enlisted the help of Italian architect Gae Aulenti for their designs. They were the LV-I World Timer and the Monterey II Alarm Travel Watch, both impressively conceived even by today’s standards but were powered by quartz movements.

It was only in 2002 when Louis Vuitton established a watchmaking division, which was based within the facility of its stablemate TAG Heuer in La Chaux-de-Fonds. It launched the now-iconic Tambour, a distinctive drum-shaped watch with slopping flanks, that same year. Given that travel is synonymous with Louis Vuitton, the watch was a GMT, equipped with an automatic movement. The following year, it introduced the COSC-certified Tambour Chronograph LV277 and, this time, the trunk maker turned to yet another of its corporate siblings for its movement and was endowed with the legendary Zenith El Primero.

In 2009, just as waves of innovation — technical, aesthetic and conceptual — unfolded in the wider watch world, Louis Vuitton unveiled the Spin Time. In place of a traditional hour hand were 12 miniature rotating cubes that rotated one by one to reveal the new hour, offering an innovative take on the jumping hour complication. It was conceived by Michel Navas and Enrico Barbasini, founders of the Geneva-based atelier La Fabrique du Temps. The immensely talented duo is best known in modern times for having developed the Tourbillon Double Spiral caliber for Laurent Ferrier, their former colleague at Patek Philippe, and subsequently, the Micro-Rotor, one of the finest, most elaborately constructed time-only automatic movements in watchmaking, equipped with a natural escapement.

Just two years later, in 2011, Louis Vuitton acquired the technical powerhouse, which gave it an in-house capability beyond its peers, particularly in terms of exotic and highly complex watchmaking. To make this fully known, Louis Vuitton unveiled the Tambour Minute Repeater that same year. The watch combined a GMT and minute repeater, which chimed the wearer’s home time, as indicated in an aperture at the center of the dial.

Less than half a year later in 2012, it snapped up specialist dial maker Léman Cadran, which gave it a distinct advantage over not only its peers but most watch brands. Finally, in 2014, the entire watch division was consolidated in a brand-new, 4,000-square-meter manufacturing facility in Meyrin, on the outskirts of Geneva.

The years that followed were spent reaching for the stars, beginning with the Voyager Flying Tourbillon Poinçon de Genève, a drastically openworked movement that attained the Geneva Hallmark, which is an achievement it shares with only six other watch brands, to the Tambour Twin Chrono, a dual chronograph with a differential display to measure split time and the distinctive Escale Worldtime that features three concentric disks for the hours, minutes and cities with the latter hand painted with the city abbreviations and corresponding nautical flags inspired by the monograms relief sculpture of a skull with an enameled snake coiled around it. When a serpent-shaped pusher at the side of the case is depressed, the minute repeater chimes the time while the dial springs to life. The snake moves its head to reveal a jumping hour aperture in the shape of a Louis Vuitton monogram star on its forehead while the tip of its tail moves across the retrograde minute scale just below the hour glass that measures power reserve. At the same time, the skull winks to reveal a monogram flower in its right socket and its jaw drops to reveal the words: “Carpe Diem.” The startlingly nuanced scales of the snake that incorporate the Louis Vuitton monogram were enameled by none other than Anita Porchet while the engraving was done by Geneva-based craftsman Dick Steenman.

The Voyager Flying Tourbillon Poinçon de Genève with a dramatically openworked movement that bears the Geneva Seal

The Escale Spin Time Tourbillon Central Blue, features a flying tourbillon in the center with a V-shaped carriage surrounded by 12 cubes that rotate to show the hour

The Tambour Carpe Diem is the most impressive watch produced by the maison to date in which mechanical complexity is met with a tremendous level of craft combining a minute repeater and automaton