Reference

COSC, METAS or TIMELAB? Why Chronometry Still Matters Despite Atomic Time

COSC, METAS or TIMELAB? Why Chronometry Still Matters Despite Atomic Time

My first personal encounter with chronometry as a quality differentiator was in 1999, when Omega launched its co-axial escapement at Baselworld. I had the privilege to spend the day and have dinner with the inventor, Mr. George Daniels, and be lectured on the whole evolution of his invention, through which I learned was essentially an escapement inspired by Breguet’s “échappement naturel”. It was meant to meaningfully improve the durability, extend the service intervals, and last but not least, significantly improve chronometric precision.

It has to first be said that it was Mr. Nicolas G. Hayek, then the chairman of Swiss Corporation for Microelectronics and Watchmaking Industries Ltd (formerly SMH that later became The Swatch Group), who made Daniels’ invention go from a good idea to a more efficient, industrialized version, bettering the Swiss lever escapement. All of this was made possible with Swatch Group’s mighty R&D power, bringing Omega to another level. But more on that later.

Now during that dinner in 1999, Mr. Daniels tried to explain that with the co-axial escapement, we had achieved a quantum leap and that we — Omega — needed to establish a new standard of chronometer certification. “You should forget COSC and create your own standard, gentlemen!” were his words. It then took 16 years to launch the Master Chronometer certification. That was not only due to the legendary slowness of the Swiss, but was largely in part of the complexity of the whole operation. And certifying more than half a million watches per year is another challenge, much more sending a few watches per year to an observatory.

Personally, I closed the learning loop when we started working on the Laurent Ferrier micro-rotor equipped with the “échappement naturel” with our partners at La Fabrique du Temps. Michel Navas and Enrico Barbasini, the two founders of the specialist manufacture, did attempt to explain to me about the advantages of one of the four versions Breguet had imagined for his échappement naturel. During that crash course in horological escapements, I finally connected the dots. Hence it took me more than a decade to fully understand what Mr. Daniels had spent a whole day explaining — interrupted by a few gin and tonics.

The Origins of Chronometry

Let me start from the very beginning. In 1969, Seiko launched the Astron quartz watch on Christmas Day and within a short time, everything changed for the Swiss watch industry. For a fraction of the amount needed to buy a mechanical chronometer, you could now buy a watch which didn’t need to be wound manually or by wearing it, and which was more precise than the most precise Swiss mechanical watch.

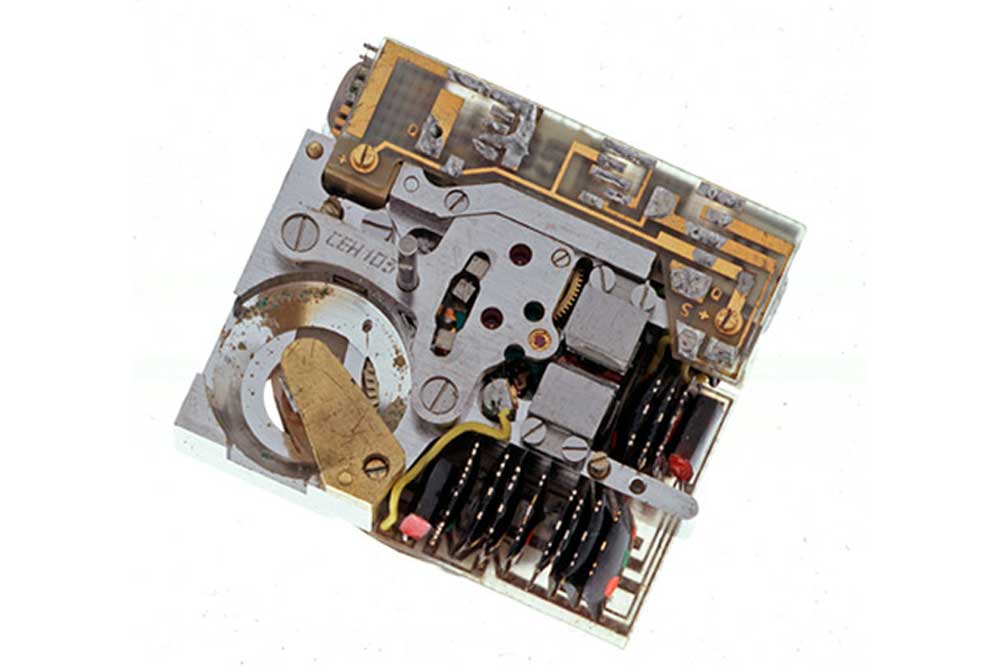

It’s not that the Swiss were really lagging behind in terms of technology, for they were the ones who invented quartz before the Japanese did. The Swiss had presented the world’s first quartz wristwatch with the Beta 1 movement in 1967, which was developed at the now-defunct Centre Electronique Horloger (CEH), although they took some time to come up with the industrialized branded product which would become the Beta 21 movement.

In fact, 20 Swiss watch brands — Rado, Bulova and Patek Philippe, just to name a few — each came up with their own version of a quartz watch at the Foire Suisse de Bâle (ancestor of the now-defunct Baselworld) in 1970, a few months after the Japanese did. The problem the Swiss manufactures faced then was not so much one of timing when it came to marketing their innovation, but it was the technology itself that was inferior in terms of battery autonomy.

The first chapter of the Swiss quartz was short-lived and after 6,000 Beta 21 movements were produced, they had to rethink their strategy. By then, Seiko’s quartz watches were already conquering wrists around the world.

Despite what’s been written, the Quartz Crisis (1975–1985) was only partly caused by a technological disruption and an industry not capable or willing to address the threat. On top of that were unfavorable exchange rates for the Swiss franc, the Oil Crisis (1973) and other geopolitical threats that further weakened the mechanical watch industry to the extent that it almost disappeared.

Until Swatch launched the ultimate weapon to counter the Japanese threat in 1983 by re-inventing the entry-level wristwatch through another technological disruption (with 51 parts for the watch and numerous patents applied), running provocative communication campaigns, and relentless product launches, the Swiss watch industry was almost out of business.

The Rebirth of Mechanical Watchmaking

Once the threat at the bottom had been addressed with the strategy laid out by former Swatch Group Chairman, Mr. Hayek Sr. (who was known to say that you shouldn’t allow your competitor to take “the next layer of the cake”), mechanical watches became a topic again. Alongside Swatch Group and its flagship brand Omega, niche brands like Blancpain with industry legend Jean-Claude Biver at the helm and Ulysse Nardin managed by Rolf Schnyder were also promoting the values of traditional watchmaking.

Much more than reconstructing production capacities that had been all but decimated by the Quartz Crisis, the new stars of watchmaking rebuilt an image of precision and accuracy even though these had lost their functional values. A quartz movement has to comply with much tighter precision criteria than mechanical watches to get a chronometer certification with an average daytime rate of only -/+ 0.07 seconds per day to be compared with the latter’s -4/+6 seconds per day, or 10 seconds a day deviation.

Hence, a quartz has to be 71 times more precise than a mechanical chronometer. Anyone understands that the two types of movements, namely quartz and mechanical, don’t play in the same league in terms of precision or autonomy — a quartz battery will ensure an autonomy measured in years, compared with days (industry standard is at least two days) for a mechanical movement.

So, what’s the fuss about being chronometer certified?

Being a car aficionado, I’ve always liked to draw parallels with the watch world. Just as some people like to think that driving a manual geared car is the more authentic way, winding your watch by turning the crown creates a bond with your watch that goes beyond just practical considerations.

The sight and sound of gears in motion create that magic moment that still evokes a child-like sense of wonder. True watch collectors acknowledge the achievements of watchmakers when it comes to precisely regulating a mechanical movement as compared to producing electrical circuits for quartz movements. Enhancing a mechanical movement by making it work as precisely as possible is the ultimate goal for any watchmaker. And that brings us to chronometry and the related topics of magnetism and craftsmanship.

Chronometer Certification and Hallmarks for Horological Excellence

Chronometer certification became an issue when pocket watches became mass produced, and the brands were competing with marketing driven concepts to highlight the quality of their products. That was the time when controlling authorities were created, around the 1880s, with certification offices, and more importantly, chronometrical observatories such as Geneva, La Chaux-de-Fonds and later on Besançon in France.

The main purpose of all those official certification authorities was to give a higher degree of horological legitimacy to the higher-end products, hence the more expensive watches. When wristwatches started to become a mass product in the 1930s and drove the pocket watches out of business, chronometric precision, and the way to measure and certify it, remained a hot topic for the watch brands. Back then, watch brands would emphasize a lot on the value of a watch being an instrument or a tool, at least for men’s watches (when watches were still categorized by gender).

The same narrative is still being used especially by Rolex to highlight the excellence of its products by printing “Officially Certified Superlative Chronometer.”

The Bastions of Precision and Accuracy

If anyone still questioned the relevance of chronometric precision in the 21st century, the recent announcement by Omega of its new Laboratoire de Précision should be a statement strong enough to lift the remaining doubts. Omega has always been amongst the relevant brands in the field of chronometric certification together with Rolex, Longines and Zenith from the 1930s until the end of the chronometry competitions in 1969.

Omega has rolled out a long-term strategy, working with the Swiss Federal Institute of Metrology, or METAS, for the launch of the Master Chronometer in 2015. This was intended to position the brand above the main Contrôle Officiel Suisse des Chronomètres, or COSC, and give it a major competitive edge by performing a double certification. The METAS Master Chronometer certification was never meant to remain an exclusive Omega hallmark; on the contrary, Omega was open to any other brand wanting to set up the laboratories needed to get the METAS stamp.

METAS and Master Chronometer

Swiss Federal Institute of Metrology, better known as METAS, is the guardian of measurement units in Switzerland, and its conformity assessment body ensures that the watches subjected to METAS testing meet the highest standard of chronometry certification. Even though the METAS Master Chronometer certification is meant to be accessible for any brand, there are currently only two brands submitting their watches for the tests: Omega, with almost 100 percent of its mechanical watches, and Tudor, with one METAS Master Chronometer caliber (the MT5602-U) which is used for the Black Bay. Tests are performed at Omega’s premises under the supervision of METAS officials which are employees of the Swiss confederation. The same applies to Tudor.

The METAS Master Chronometer certification is beyond question the most stringent hallmark that a wristwatch can get, with a double certification both issued by official bodies: COSC, for the chronometer certification of the movement, and METAS, for the certification of the chronometric precision of the watch (and not only the movement) and the resistance to magnetic fields to 15,000 gauss on top of testing the power reserve, durability and waterproofness. There is no shock proof testing. Overall, the certification comprises eight different tests which are performed over a period of 15 days following the ISO 3159 procedure.

The New Laboratoire de Précision

Omega has now decided on upping the game with the launch of the Laboratoire de Précision, which is meant to replace the COSC certification of its movements. Following the same certification procedure of the ISO 3159, the new testing and certifying capacities are duly authorized under the very stringent criteria of the Swiss Accreditation System (SAS) which is a state-controlled authority.

The major difference between Laboratoire de Précision and the COSC certification is that the movements tested by the former will be under continuous monitoring for 15 days and not “only” optically controlled by a visual mark every 24 hours when the seconds hand passes the 12 o’clock index. The ISO standard 3159 specifies that a chronometer is a “precision wristwatch regulated for different positions and for various conditions of use.”

Accordingly, Laboratoire de Précision’s testing method seeks to meet, or even surpass, the required standard by measuring every beat of each movement, with a measurement accuracy 10 times that of the industry standard. Initially, the COSC was meant to certify only complete watches or watch heads, and not the movement only.

Today, however, a large part of watches bearing the COSC hallmark have only had their movements certified before being cased. In summary, the new certification authority, Laboratoire de Précision, will ensure a higher measurement accuracy but will keep the timing precision at the Omega standard of 0/+5 seconds per day deviation, which is twice more stringent than the ISO 3159 measure which allows for 10 seconds per day (-4/+6 seconds per day).

Beyond the obvious advantages of integrating the whole testing supply chain in-house and thus avoiding unnecessary handling (often detrimental to the movements’ accuracy), the brand reduces its carbon footprint (it’s worth mentioning that more than 1,000,000 mechanical movements are tested each year by the COSC), but foremost, it gets a lot of data. And that’s where the manufacturing excellence stands out when you keep improving the quality of your products by consistently measuring them.

TIMELAB and the Poinçon de Genève

A coveted quality hallmark that’s probably the one with the most credibility around the world is the Poinçon de Genève (Geneva Seal) which is being certified by TIMELAB, a public foundation governed by Law I 1.25 of the canton of Geneva. The Poinçon de Genève certification encompasses three parameters:

• Provenance: The movement’s components need to be finished and decorated following stringent rules by an atelier which needs to be located in the canton of Geneva.

• Traditional craftsmanship: Although TIMELAB can authorize the use of innovative materials, it intends to keep traditional methods by, for example, forbidding the gluing of the balance spring.

• Reliability:

◦ The functions of the watch are being tested, e.g. the chronograph or the perpetual calendar functions.

◦ The water resistance is being tested.

◦ The accuracy is tested by visual testing on day 0 and again on day 7 and the deviation must be within one minute. This makes it a more stringent requirement — allowing for 8.57 seconds per day — than COSC which allows for a daily -4/+6 seconds per day (10 seconds in total) deviation.

Contrôle Officiel Suisse des Chronomètres

The Contrôle Officiel Suisse des Chronomètres, or COSC, is the most known controlling authority in the watch world, and certifies both movements and cased watches based on the international ISO norm 3159, which sets the rules of chronometer certification. It is often wrongly seen as a second-class chronometer certification; in fact it’s not, because even the two brands doing the METAS Master Chronometer certification — Omega and Tudor — as well as Rolex with its Superlative Chronometer certification, have their movements first certified by the COSC, on which they add the certification of the watch head.

As such, the chronometer certification of these brands is a double-layered quality hallmark, with the additional criteria of certifying the watch head (the complete watch), and testing the power reserve, waterproofness, durability and resistance to magnetic fields.

Fondation Qualité Fleurier

The Fondation Qualité Fleurier, or FQF, is an appropriate approach to certifying timepieces not only for timekeeping precision, but also includes other valuable parameters. Each watch must be 100 percent manufactured in Switzerland, the finishing of the components must fulfill certain criteria (just as with the Poinçon de Genève), the movement must be COSC certified, the watch has to be tested to resist shocks and magnetic fields via the Chronofiable test, and finally, it must also prove its accuracy to 0/+5 seconds per day with 24 hours of testing that reproduces what it would endure on a wearer’s wrist.

This certification was initially set up in 2004 by the watch manufacturers established in the Fleurier valley (in the canton of Neuchâtel) and the fine league was composed by Chopard L.U.C, Bovet, Parmigiani and Vaucher. Even though the certification is a very credible way of ensuring the quality of manufacturing, the provenance and the finishing quality of the parts, on top of undergoing a series of tests and being double certified, the hallmark never gained the visibility it deserved.

The reason being probably that Fleurier is not a household provenance, unlike what Geneva and its “Poinçon de Genève” represents. It is interesting to note that Chopard also complies with the Poinçon de Genève hallmark on its L.U.C watches, which are amongst the finest timepieces of the Swiss watch industry.

Observatoire de Besançon

Besançon played a very important role for the French watch industry by certifying many pocket watches from brands like L.Leroy & Cie., and later on for wristwatches. The chronometer certification of the Observatoire de Besançon was reborn from its ashes in 2008 by a clever independent watchmaker — Kari Voutilainen — who understood, long before any of his competitors in the league of artisan watchmakers, that chronometry could become a competitive edge. The prestige of the punch “tête de vipère” (viper’s head) stamp of the Observatoire de Besançon on the movement of any certified watch is definitely a mark of excellence for a watch brand or artisan watchmaker.

Today, quite a few independent watchmakers are using Besançon’s services to certify their watches and issue a “bulletin de marche de chronométrie” (chronometry bulletin), which is a valuable document for the client. Kari Voutilainen, Laurent Ferrier and Rexhep Rexhepi are amongst the artisan watchmakers sending their watches from Switzerland to France to get their watches chronometer certified if the client requests it.

Dominance of the Heavyweights

The precision of mechanical watches might seem an outdated topic that faded when the chronometry competitions went out of fashion in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but achieving ultimate precision is still the central communication backbone of Rolex and Omega. When Rolex claims that its watches are “Superlative Chronometer Officially Certified,” attaching a green seal with the embossed claim, it’s showing that precision is a key founding value of the brand.

Omega has chosen to name its chronometry timepieces “Master Chronometers” which sounds equally strong, although the main difference between the two brands is that one goes through a Swiss certification authority. What both brands have in common (and we should add Tudor to the count, having one model being METAS Master Chronometer certified as well) is the seriousness of their certification methodology.

Certifying a few dozen watches with a chronometer certification, as some independent watchmakers do, deserves credit, but when you certify all your mechanical watches with the coveted hallmark of chronometer, as Rolex and Omega do, then you are in a totally different ballpark. We are talking about hundreds of thousands of watches which need to pass a certification which lasts 15 days.

After launching the Spirate last year to allow for a better adjustment of the hairspring, Omega is now pushing the boundaries even further with the Laboratoire de Précision. Interestingly, the Spirate is not an entirely new concept (even though the Swatch Group has applied for a patent) because the idea dates back to the 1920s, when a watchmaker of La Chaux-de-Fonds, Charles Le Brun, had the idea of having three screws on the balance wheel, giving the watchmaker the possibility to fine-tune the attaching points of the hairspring. Nevertheless, the Spirate has allowed Omega to achieve even better chronometric results with a deviation of only 0/+2 seconds per day.

Resistance to Magnetic Fields

Achieving chronometric precision implies not only precise manufacturing of the components and a meticulous regulating of the movement, but also mastering the detrimental impact of magnetic fields. And on this turf, there aren’t many players left, at least not those that are playing at the same level as Omega, Tudor and Rolex.

The first two brands comply with an extremely impressive norm verified by METAS set at 15,000 gauss, whereas Rolex doesn’t communicate the value its watches have to comply with in terms of magnetic field resistance. The value of magnetic resistance a watch has to comply with is impressive, but not so relevant in everyday life where the highest values of magnetic fields are around 1,500 milligauss (1 gauss = 1,000 milligauss). The more common standard for certifying the resistance to magnetic fields is set at 16,000 A/m which translates into 200 Gauss.

This standard ISO 764 value is in fact used by TIMELAB for its “OC+” certification, which in contrast to the METAS certification, seems low but it complies with most situations in our daily life. Silicon hairsprings and the use of antimagnetic materials for the other parts of the escapement are key to making a watch antimagnetic, but they require manufacturing means which may not be accessible for smaller brands.

For example, Rexhep Rexhepi’s Chronomètre Antimagnétique utilizes antimagnetic stainless steel for the case, with a hand finished movement protected by a Faraday cage. These are reminiscent of the watches used by explorers of the North and South Poles in the mid 20th century to avoid the magnetic fields at the poles, but certainly are not innovations like the silicon hairsprings used by Omega, Tudor and Rolex.

Final Thoughts on the Future of Chronometry

It might be a good idea to consider revising the standards applied to chronometric precision, which date back to 1976, to create a new and official standard. In fact, it’s what Omega has done with its METAS Master Chronometer certification, which sets it above the COSC certification.

With today’s machining precision, the performances that can be potentially achieved are substantially better than 50 years ago, and that should be taken into account when talking about timekeeping precision. However, one thing we should avoid at all costs is to confuse the clients with too many standards and certifications. Performing chronometer certification for hundreds of thousands of timepieces a year requires very serious manufacturing capacities, and hence, massive investments are needed which will separate the wheat from the chaff, at least in this respect.