News

Introducing the First-Ever Royal Oak Selfwinding Flying Tourbillon

Introducing the First-Ever Royal Oak Selfwinding Flying Tourbillon

At the tail end of the Quartz Crisis, however, Audemars Piguet recognized that “business as usual” was not going to work if the Swiss Watch industry wanted any sort of edge ahead of the Japanese whose electronic watches had taken the world by storm. It is with this in mind that the watchmaker launched one of its most audacious creations in 1977, the 36mm and 7mm thick, ref. 5548 Perpetual Calendar powered by the calibre 2120/2800, designed by the one and only, Jacqueline Dimier. But the 5548 isn’t the only project that Audemars Piguet took on to tackle these dark days.

Before we discuss chapter two of this story, first an extract from an earlier article published on Revolution.Watch, about two gentlemen: movement constructor Maurice Grimm and project manager André Beyner of Ebauches SA.

How the World Got Its First Automatic Tourbillon Wristwatch

While companies were collapsing in the Jura, in Neuchâtel two engineers had a vision of how the industry could marry the skills of Swiss watchmakers with quartz technology. Remember, this was the end of the 1970s and most of the great Swiss watchmakers had been making slim, elegant watches for a few years and these were at the opposite end of the timekeeping spectrum to the average quartz watch. The two watchmakers – movement constructor Maurice Grimm and project manager André Beyner of Ebauches SA – had an idea for a quartz watch which would not only be thin and elegant, but one which would change the way watches were made.

Any watch comprises four distinct components: a power source; a regulating mechanism, which turns that power into units of time; a transmission system connecting the regulator; and the final component, the display. The brilliant idea of the Neuchâtel team was to split the components horizontally rather than stacking them vertically on top of one another.

The new watch design was rectangular, and the case was split into three areas – a central dial area and two smaller areas, one above and one below the dial – by placing a tiny battery in one area and the electronics in the other meaning that the overall depth was governed only by the height of the centre pinion and the single wheel below it.

The reduced height was further aided by the decision to abandon the centuries-old convention of plates and bridges. The case was machined from a solid piece of gold, resulting in a shape like the lid of a shoe box, the components were fitted into their respective areas, then the dial and hands and finally a thin sheet of sapphire glass was fitted to close the watch.

At 1.98mm thin, the (aptly named) Delirium was the slimmest watch in the world and sold well, but the truth was that the small market for high-end quartz watches was not going to save the Swiss watch industry and, as if to emphasise that fact, Beyner and Grimm both left Ebauches SA. But with time on their hands, they looked around and noticed that two companies in Switzerland were now getting into the EDM business and this gave them an idea. They went back to work, and over the next few months, worked this idea into a patentable form, filing Swiss patent 007961/1980 on 24 October 1980; their design for an ultra-slim, self-winding wristwatch.

By using the same idea as in the Delirium (that of rearranging the normal components in an unconventional way they were able to drastically reduce the height of the watch. While dispensing with plates and bridges is possible in an electronic watch, it had never been tried in a mechanical one. The breakthrough was to use the case as the mainplate of the movement with a single large bridge as the other support for the pinions. The other eureka moment came with the realization that a winding rotor does not necessarily have to go through 360 degrees, as long as it can move the winding wheel one click at a time.

With this prototype, Beyner and Grimm succeeded in pushing watchmaking’s boundaries, producing the world’s first automatic-winding, ultra-thin tourbillon. At only 2.7mm thick they established a record by integrating the movement with the case back (Picture courtesy of Phillips)

The patent was assigned to Ebauches SA, which decided that the market for slim gold dress watches had dried up and that there was little point in manufacturing it. They also had the problem of being a company that made movements for other companies to install in cases. That was not a possibility with Grimm’s idea – in essence there was no movement, it could only exist as a complete watch and Ebauches SA had no experience in selling watches so quietly shelved the idea and Beyner and Grimm went back to looking at what was not only possible, but practical.

Three years later, as Electro Discharge Machining (EDM) precision developed further, Beyner and Grimm came up with an intriguing idea; what if they tried to use a machine to make a tourbillon cage? No milling or boring machine was capable of this, but close tolerances and excellent surface finishing were the raison d’être of EDMs. So they gave it a try, and, in just over a year, they had a working tourbillon – and not just any working tourbillion: As a “proof of concept” they had made the world’s smallest tourbillon, only 7.2mm in diameter and weighing just over one tenth of a gram (0.123 grams to be precise).

The dial of the Beyner and Grimm prototype sold by Phillips in May 2016 clearly shows the logo of Ebauches SA or, as it later became known, ETA (Picture courtesy of Phillips)

Normally such prototypes are kept locked away in the manufacturer’s archives, or even destroyed, but in this case Beyner and Grimm’s final prototype appeared at auction as lot 200 in the May 2016 Phillips Geneva Watch Auction: THREE, complete with much of the documentation. The watch fetched CHF 30,000.

But while Beyner and Grimm knew the watch could be made in quantity if needed, they realised that there were two vital questions. Firstly, who would make it – none of the Swiss watch companies had yet made the investment in the new machinery. Secondly, was there actually a market for a tourbillon wristwatch – not only had one never been sold commercially, but fewer than 20 wristwatch tourbillions had ever been made, so this was probably the very definition of an untried market.

The first hurdle to be crossed was choosing a manufacturer. It could only really be one of the three grande maisons – Patek Philippe, Vacheron Constantin or Audemars Piguet. Patek Philippe was ruled out as too conservative and of the remaining two, Audemars Piguet was the obvious choice as the new watch was very slim and was known for ultra-slim movements, the “9 douzième” holding the record as the world’s thinnest movement for many years. In addition, Audemars Piguet was still run by the founding family and so the decision path was very short.

The centrepiece of the watch’s dial is the tourbillon aperture – a familiar sight today, but a rarity in the 1980s. The tourbillon represents the sun with the rays crossing the dial from this point. Inspired by Egyptian carvings, the watch became known as “Ra” – the sun god

It is interesting to look at the differences and similarities between the production watch and lot 200. The major difference is that the production watch is turned through 180 degrees compared to the prototype, the production version has the tourbillon at the top and the pendulum at the bottom, which is not only aesthetically pleasing but gives prominence to the tourbillon, which (after all) was its key feature. Obviously, the watch does not bear the name Audemars Piguet – in fact there is no name on it at all, instead where a brand name should be on the finely guillochéd dial, is an applied shield. The observant viewer will recognize the Ebauches SA logo – Beyner and Grimm’s previous employer, now known as ETA.

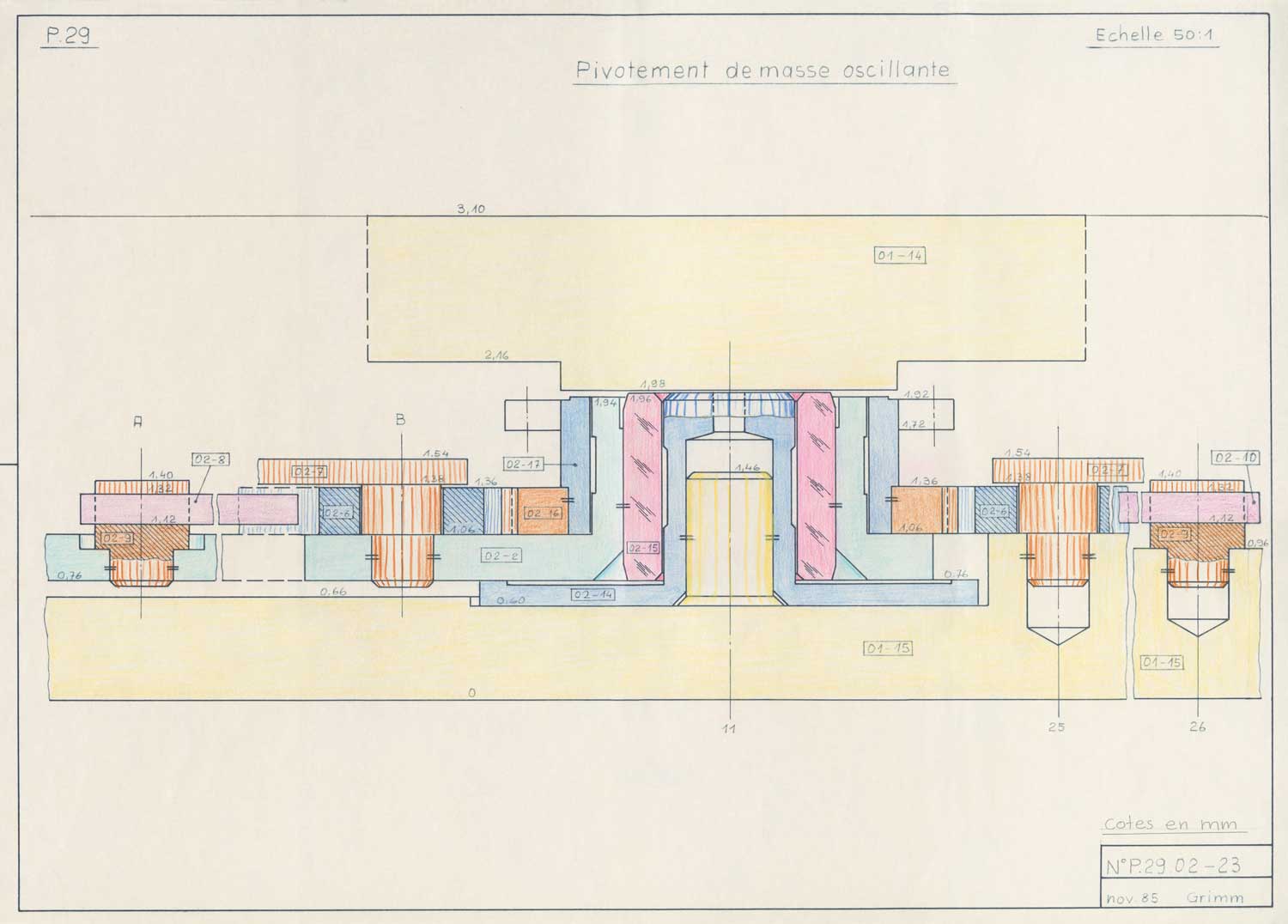

Diagram showing the pivot of the oscillating mass for the automatic winding system, courtesy of Audemars Piguet Archives

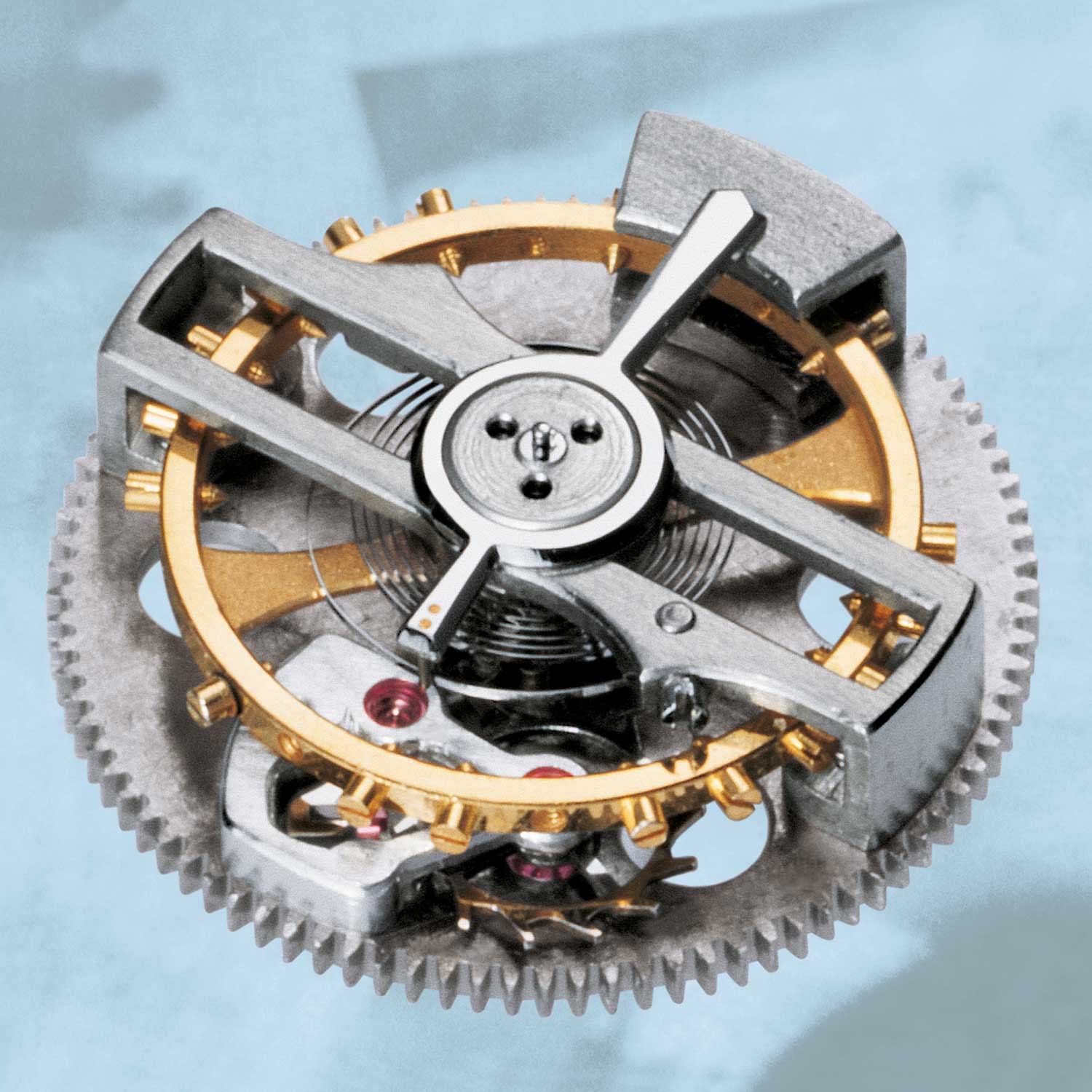

The tourbillon mechanism of the of the Calibre 2870 which weighed but a mere 0.123 grams)

The Royal Oak Tourbillons Through Time

At this time, the man at the helm of Audemars Piguet was none other than Georges Golay. Under his care the watchmaker had already launched two legends in the making: the 1972 Royal Oak ref. 5402 and the later 5548 Perpetual Calendar. This was against this backdrop to which Beyner and Grimm had brought Audemars Piguet their self-winding tourbillon prototype.

Golay in turn, took the knowhow and handed it to a particular Serge Meylan, a young movement constructor who had recently joined workshops. His task was to take Beyner and Grimm’s prototype and create a watch that that the watchmaker could call its own.

Young Meylan took on the challenge and possibly one of the world’s smallest tourbillons (7.2mm diameter) and gave it a titanium cage for stability and lightness. The use of titanium here was another first in the world of watchmaking.

Selfwinding tourbillon prototype. 18-carat yellow gold. Prototype made circa 1985. Audemars Piguet Heritage Collection, Inv. 538.

Between 1986 and 1999, the Model 25643 powered by the calibre 2870 as it was named, Audemars Piguet delivered approximately 401 of these watches. The Audemars Piguet 20th Century Complicated Wristwatches book records further, “In the same way as the perpetual calendar in 1978, the tourbillon introduced in 1986 forged a new path for the entire high-end watchmaking sector, which renewed ties with this escapement specialty, interpreting it in countless different ways. At Audemars Piguet, several generations of tourbillons succeeded calibre 2870, displaying ever greater robustness and reliability, produced since the 1990s in workshops in Le Locle under the supervision of Giulio Papi, and often combined with other complications such as the chronograph, the calendar or the repeater.”

Selfwinding tourbillon. 18-carat yellow gold case No 296. Calibre 2870. Model 25643BA with lug bar cover. Watch sold in 1990. Audemars Piguet Heritage Collection, Inv. 1057.

Royal Oak Tourbillon. Selfwinding, date, 52- hour power-reserve indication. Movement No 386194, 18-carat pink gold case No D99406, 01. Calibre 2875. Model 25831OR issued in a fivepiece limited edition. Audemars Piguet Heritage Collection, Inv. 910.

2012: The Audemars Piguet Openworked Extra-Thin Royal Oak Tourbillon 40th Anniversary Limited Edition, in a 41mm 950 platinum case powered by the hand-wound Manufacture Calibre 2924; issued in a limited run of 40 pieces

2012: Celebrating the Royal Oak's 40th Anniversary, Audemars Piguet introduced the Royal Oak Extra-Thin Royal Oak Tourbillon, with a 41mm 18-carat pink gold case powered by the Hand-wound Manufacture Calibre 2924

in 2018, Audemars Piguet introduced their first use of the flying tourbillon mechanism with the Royal Oak Concept Flying Tourbillon GMT

A closer look at the 2018 Royal Oak Tourbillon Extra-Thin's Tapisserie Evolutive dial. (© Revolution)

Royal Oak Selfwinding Flying Tourbillon // 41 mm ref. 26530ST.OO.1220ST.01, featuring a smoked blue dial with “Evolutive Tapisserie” pattern, powered by the selfwinding Manufacture Calibre 2950

Royal Oak Selfwinding Flying Tourbillon // 41 mm ref. 26530OR.OO.1220OR.01 featuring a smoked grey dial with “Evolutive Tapisserie” pattern, powered by the selfwinding Manufacture Calibre 2950

Royal Oak Selfwinding Flying Tourbillon // 41 mm ref. 26530OR.OO.1220OR.01 featuring a smoked grey dial with “Evolutive Tapisserie” pattern, powered by the selfwinding Manufacture Calibre 2950

Royal Oak Selfwinding Flying Tourbillon // 41 mm ref. 26530TI.OO.1220TI.01, featuring a sandblasted slate grey dial with snailing in periphery, powered by the selfwinding Manufacture Calibre 2950

Royal Oak Selfwinding Flying Tourbillon // 41 mm ref. 26530TI.OO.1220TI.01, featuring a sandblasted slate grey dial with snailing in periphery, powered by the selfwinding Manufacture Calibre 2950

Movement

Selfwinding Manufacture Calibre 2950; hours and minutes; flying tourbillon; 65-hour power reserve

Case

Diameter: 41mm; thickness: 10.4mm; stainless steel, titanium or 18K pink gold; water resistant to 50m

Bracelet

Metal bracelet matching case with AP triple-blade folding clasp

Price

Stainless steel: CHF 129,000

Titanium: CHF 129,000

18K pink gold: CHF 159,000[/td_block_text_with_title]

Audemars Piguet